Credit Suisse Tells Bloomberg: “Mortgage Principal Cuts Don’t Help Homeowners?”

Believe it or not, I’m not an easy person to shock or offend. No one that knows me would ever say that I possess delicate sensibilities, or anything close. For example, the only thing I found at all shocking upon learning that Newt Gingrich had asked his now ex-wife if they could have an “open marriage,” was that there were more than two women (or even one gay man), that would even consider having sex with Newt.

But, when I read Bloomberg’s headline yesterday, “Mortgage Principal Cuts Don’t Help Homeowners, Says Credit Suisse,” I have to admit that I found myself recoiling in total shock that, in view of what’s happening today in the housing market, anyone would put forth such an utterly preposterous argument.

Here’s the beginning of the Bloomberg piece, you can read the rest later.

Reducing mortgage balances is a risky idea that hasn’t been shown to keep borrowers who owe more than their property’s worth in their homes, according to Credit Suisse Group AG. (CSGN).

Of the 11 million of “underwater” homeowners, about 6.5 million have never missed a payment and 2 million more are making on-time payments after a delinquency, said Dale Westhoff, the bank’s global head of structured products research. Widespread principal reductions may drive defaults “much, much higher” as borrowers seek the aid, he said.

“We’ve never done this before; we don’t know what the risk is,” Westhoff, a top-ranked mortgage-bond analyst in polls by Institutional Investor magazine for 15 years in a row while at Bear Stearns Cos., said today at a briefing for reporters in New York. Along with creating so-called moral hazard, the step may also tighten lending by forcing banks to offer “price protection” to borrowers, he said.

Credit Suisse’s view puts it at odds with Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William C. Dudley; Amherst Securities Group LP analyst Laurie Goodman, a member of the Fixed Income Analysts Society’s Hall of Fame; and hedge-fund manager Greg Lippmann, who last year advocated principal reductions, citing data from his former employer, Deutsche Bank AG.

Pretty offensive stuff, don’t you think… as you sit there reading this in your home that’s underwater by six figures and going down further every day? Feel a little like wringing the guy’s neck that said it? Yeah, well… me too.

Instead, I’ve written a corresponding article that I’d like to see Bloomberg run in the interest of being… what should I say… fair and balanced? If you want the full impact, however, go back and read the Bloomberg version above one more time, then continue…

Not Recognizing Losses and Unlimited 0% Interest Loans Don’t Help Banks, Says Credit Slush

Suspending accounting rules is a risky idea that hasn’t been shown to keep banks that borrowed more than their assets are worth from becoming insolvent, according to Credit Slush Fund PIG.

Of the 11 most bailed out banks, about 6 have never been able to make their payments, and 2 more are making on time payments after being allowed to become bank holding companies in name only so they could borrow unlimited amounts from the Fed’s discount window at zero percent interest, said Bail Worstoff, the consumer’s global head-case for unstructured thinking.

Widespread zero interest borrowing and the ongoing suspension of accounting rules that allow banks to push off the recognition of losses far into the future may drive insolvency rates “much, much higher” as banks become entirely dependent on the unrealistic and inappropriate aid.

“We’ve never done this before; we don’t know what the risk is,” Worsthoff, a top-ranked banking behavior analyst in polls by Concerned Citizens with Common Sense for 15 years in a row, said today at a briefing for reporters in New York. Along with creating so-called “moral hazard,” these steps are also likely to perpetuate the irresponsible risk taking and amounts of leverage taken on by banks, which is what caused the global financial crisis in the first place, and would force congress to once again be unable to offer “any protection” to taxpayers who will be on the hook when the bankers invariably become insolvent once again, he said.

Credit Slush Fund’s view puts it at odds with Federal Unreserved Chair Ben Bailsnakee, Treasury Secretary Skim Getmore, Scary Summers, a member of the Fixed Outcome & Opacity Legion (“FOOL”); and sludge-fund manager Greed Hittmann, who last year advocated unlimited and unreported zero interest borrowing, undisclosed backdoor bailouts, and the elimination of all bank accounting and reporting requirements, citing data from his former employer, Deushbag Bank PIG.

First of all, the idea that reducing the dollar amount someone owes on his or her mortgage isn’t helpful to the homeowner… well, it’s simply a goofy thing to say. I mean, it has to be a question of degree, right? Like, reducing someone’s $100,000 balance by $1 wouldn’t be terribly helpful, I understand. It’s the Sorites Paradox, I suppose… which back in my debate-the-useless days as an undergrad we used to refer to as the “Paradox of the Heap.”

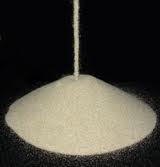

(Assuming you have no idea what I’m talking about, but would like to… the Paradox of the Heap deals with a heap of sand from which one grain of sand at a time is removed. The first premise is that one million grains of sand is a heap of sand. And the second premise is that a heap of sand minus one grain of sand is STILL a heap of sand. With me so far? Good.

So, the question is… when a single grain of sand is all that’s remains, is it STILL a “heap of sand?” If you answer yes, then you sound ridiculous because a heap is defined as a group of things placed or thrown on top of each other.” And if you answer no to that question, then the follow-up question is when did it stop being a heap… when it was two grains of sand… three… four… 100?

I can’t remember exactly, it’s been too many years… but I think after that you either run screaming from the room, beat the crap out of your roommate for dragging you into this inane conversation, or take a hit off the bong.)

Am I getting my point across here? Or am I being too subtle?

Because I often worry that my use of humor or sarcasm either goes over too many heads or is solely as thought of as being entertainment… instead of as the less-than-veiled threat to societal tranquility that was my actual intention. (That was supposed to be funny, people… stay with me, okay?)

After reading the Bloomberg article, it occurred to me that this was not the first time I was being shocked at the hubris of Credit Suisse’s conclusions allegedly derived from some review of distressed homeowner data. The last time it happened was more than two years ago, November 2009, when I wrote about it in an article titled: “Why Banks Are Better at Making Loans Than Modifying Them.”

Back then Credit Suisse in conjunction with UBS, published a statistic saying that loan modifications were re-defaulting in 60 percent of cases after just 10 months… the clear implication being that loan modifications didn’t work, so better for all involved to simply foreclose. It took some digging as I recall, but in the end it came out that in 2008… 60 percent of the loans modified ended up with higher monthly payments than before they were modified… which would explain the 60 percent re-default rate quite handedly.

It’s been a while, but I remember having an exasperating conversation with a banker during which I was trying to make the point that when the payment amount increases, it should not be called or classified as a “loan modification.” The banker I was talking to… bless his heart… was trying to patiently explain to me why in point of fact, it was a “modification” of the loan and therefore had to be classified and reported as a “loan modification.” (Amazing I’m still alive, don’t you think? Or that the banker is… I’m not sure which.)

I replied that it didn’t matter. What mattered is that if I were to line up 10 million homeowners in this country, and ask them whether a loan modification makes your monthly mortgage payments go up or down, for the most part they’d all say down. Therefore, the term “loan modification” should only be used when the modification results in a reduced payment amount.

“So, what should we call it if the loan gets modified but the payments go up,” he inquired. His tone made it sound as if he was sure that he’d have me in one or two more moves on an imaginary chessboard.

“Well, I’m not sure,” I replied. “I’m not a banker or anything, and I wouldn’t want to presume to know your job better than you do by any means, but you could give some thought to calling it… oh, I don’t know… A PAYMENT INCREASE?”

Unfortunately, our conversation had to wrap up quickly after that… apparently something unexpected had come up and he had to run.

Do Principal Reductions Help, or Are they the Poster Child for Moral Hazard?

Credit Suisse should be exposed and discredited for being banking industry propagandists more than willing to risk further destruction of America’s middle class economy and our reduced standard of living before they lift a finger to make things better economically speaking. That much is certain… and all too obvious.

But, the question is: Would principal reductions help homeowners avoid foreclosure? And I want to address the substance of Mr. Dale Westhoff’s/Credit Suisse’s arguments against, lest anyone think that I’m being purely snarky about this whole thing, and therefore am in any sense being non-responsive to the issue at hand.

It’s not a simple subject, by the way. So, don’t expect me to offer an oversimplified and hence meaningless response.

Mr. Westhoff, the bank’s “global head of structured product research,” the term “research” being used extremely lightly… hinges his argument against principal reductions for homeowners as a means for preventing foreclosure on the same old argument: it will create a moral hazard.

Now, let’s take a look at what this “moral hazard” thing is all about.

Traditionally, moral hazard exists when a party can make decisions about how much risk to take on, while another party bears the costs of that risk going badly. And if that’s how we were defining it here, the only moral hazard that we’ve got to be concerned about is the moral hazard resulting from banks taking on too much risk knowing that they are “too big to fail.”

That’s the type of moral hazard that’s gotten us into this mess in the first place, and since the bailouts of banks in 2008, it’s the most significant risk we bear as a nation because if banks think they’ll be bailed out no matter what because they are too big to fail… we can all count on them needing to be bailed out again… and again… and again. So, that’s that.

Westhoff, however, is using the term moral hazard in a different sense. He’s asserting that if homeowners know that there are principal reductions available to those in default, more and more homeowners will intentionally go into default in order to get their principals reduced.

Moral Hazard and Principal Reductions

It’s shocking how little the financial services industry understands about the people it serves. One particularly telling example of this was seen in May of 2011, when one of the three major credit bureaus, TransUnion, published the results of a study that shocked the banking industry by concluding that many who have lost homes to foreclosure did so because of the downturn in the economy and not as a result of an inability to handle debt, as was previously thought.

“Lenders always try to distinguish a one-off, life-crisis event like divorce or a medical catastrophe versus people who are just ineffective at managing credit,” said Ezra Becker, TransUnion vice president of research and consulting, and one of the study’s authors.

“Our argument is that this economy disproportionately affected certain people in a way akin to a one-time crisis. Those consumers have not in fact forever changed their personal philosophy on repaying debt. It was a one-time event because of the specific and personal circumstances of the recession, and they otherwise would be good credit risks.”

What’s most amazing about the TransUnion study is that they needed to conduct a study to establish that people losing homes to foreclosure in the last few years were not irresponsible deadbeats, as the financial services industry had been assuming, but rather… well, it was the economy, stupid. That anyone in financial services needed a study to tell them that foreclosures were being caused by the credit crisis that their industry brethren created is either some distorted form of irony or disingenuous nonsense.

The banking industry’s abysmal knowledge of consumers is also readily apparent when looking at the issue of moral hazard as related to principal reductions, or the incidence of strategic default, which is when someone chooses to walk away from a mortgage even though they can afford to make their payments. These are the two subjects from which one might write a book of scary bedtime stories for bankers.

To understand this topic, first you have to understand how regular people view their homes.

The years 2003-2007 notwithstanding, homes are not seen by regular people as investments in the traditional sense, they are more like forced irrational savings accounts we inhabit. We don’t care what interest rate we’re getting on our “home/account,” but we do know the balance will be significant if we pay it off, and so they are a key component of America’s retirement plan.

Most people save money for a down payment on a house during the early part of their lives when their costs of living are relatively low. After that, if property values are rising, they become relatively more mobile because they use the equity in one home to purchase the next. It’s true that our incomes rise as we get older, but life gets more expensive over the years too.

Because the costs and expenses of buying a home and moving, if property values are falling or flat, we do everything we can to hold on to the homes we have, which is why so many underwater homeowners have applied for loan modifications even though from a strictly financial perspective, it doesn’t appear to make any sense.

It actually does make sense, however, once you understand that most people know that their only hope of buying another home will come from equity they build up in their current one. And even if they don’t build that equity as a result of market price appreciation, that’s okay because the forced savings account functionality will eventually kick in, and they’ll have the equity to move up, or an asset of significant value for unplanned emergencies or retirement years, or the foundation of an estate to leave to our children.

It should be obvious that this line of thinking is foreign to financial investment types who think in terms of comparing returns on different investments. It would be easy to show someone why it would be advantageous to accumulate wealth through a diversified set of investment vehicles while renting a home, but regular people know that they can’t trust themselves to be disciplined about saving and investing, but they can make a mortgage payment each month for 30 years because not paying that payment means disrupting their family’s tranquility… and having nowhere to live.

As a result, to stop making one’s mortgage payments on a primary residence is in general a big deal… a huge risk… you may end up losing your home… you can’t tell a living soul about what you’ve done… and your credit score goes to pot within a couple of months. It’s immensely stressful, and no one does it unless financially speaking it’s absolutely necessary, meaning that some significant life event has occurred… job or income loss, injury or illness, divorce… those are the big ones anyway.

The bottom-line is, if people can afford to make their mortgage payments… they make their mortgage payments, and this is most easily verified by looking at how low foreclosure rates have been historically, again these past few years notwithstanding, even though between 1950 and 2000, home prices nationally were flat if adjusted for inflation.

So, will homeowners in any meaningful number take the risk inherent to going into default on their mortgage in order to get their principal balance reduced? The answer should be obvious… it depends on how far underwater the homeowner is, how does the homeowner view the potential and timeframe for home price appreciation to occur, how certain is it that by defaulting they will be granted the principal reduction, and what are their options if their principal isn’t reduced and they lose their home to foreclosure.

Obviously, someone $200,000 underwater who thinks it will be 20 years before the market price appreciates by that amount, is much more likely than someone less severely underwater who views prices as coming back in five years, to walk away… or to go into default in order to try to get their bank to reduce the principal balance of their mortgage.

The other question about the efficacy of principal reductions in foreclosure prevention, applies to homeowners who are already seriously delinquent and seriously underwater, who are applying for a loan modification. Lowering this homeowner’s interest rate and extending his or her term can make the monthly payment affordable and therefore prevent a foreclosure in the short term, but the question is, by leaving the homeowner so far underwater, are we just creating a strategic default in the future?

A couple of years ago, there were a slew of articles in places like the Wall Street Journal among others, that claimed that there a rash of strategic defaulters, which are defined as people that can afford to pay their mortgage no problem, but choose not to because they owe more than the home is worth. And a couple of years ago, I wrote that strategic defaults are nonsense because no one that can afford their mortgage payments gets up on Sunday and says to their spouse:

“Honey, I realize that we can afford our mortgage payments no problem, but I was just thinking how far underwater we are and thought now might be a good time to clean out our garage, ruin our credit scores, endure the hassles of moving, and go rent a place for a five years.”

That is not what’s been happening to-date. Not that it never has or will happen, but it’s exceedingly rare. Everyone that hasn’t made a mortgage payment in months or even years is in their current situation because of money. They didn’t stop making their mortgage payment because they became upset about being underwater, nor was it because of an ability to handle debt. They stopped, in the vast majority of cases, because the economy or a life event knocked them down financially, and after using whatever savings they had, there came a day when they simply couldn’t make the payment… it wasn’t because they didn’t want to.

Optimism is a hard thing of which to let go…

I think I can remember the exact day that the dot-com bubble popped… it was April 10, 2000… and I was watching it happen on a television screen showing CNN as I waited in line to board a flight home from San Jose where I had spent the day in meetings. I remember saying to my assistant at that time, that’s it… it’s all over now, or something to that effect.

I also remember seeing the cover of Newsweek two months later; I think it was the June issue. It suggested that the tech sector would be coming back by December of that year, the obvious message being, “Don’t sell.” I laughed when I read it… but not as much as I did two years later when I was at my favorite local watering hole after work with a friend of mine. Mid-sip of my martini, he told me he was still holding onto his shares in Cisco Systems, purchased at $84, causing me to spit out my drink, choking as I laughed.

At the time, I think Cisco was trading at around $9, but my innumerate and hopelessly optimistic friend was explaining that he was only hoping the stock would return to half of its $84 price so he could then get out, losing only half of his dough. I tried to explain the math involved showing him why he should sell and take the loss on his tax returns, and he listened… but it was another year before he took the advice and I learned that optimism is a hard thing of which to let go and this crisis has been no exception.

In the early stages of the crisis, essentially everyone listened to the administration, other government sources, and financial industry PR, and as a result believed that we were experiencing a temporary downturn as had happened before… that the housing market would start to come back around in a few years. The idea of a “lost decade” was something that only happened in Japan… and everyone was saying that we were not Japan, which made sense to most folks because we cooked our fish before eating it in most if not all cases.

Recovery, the so-called experts said, would come by the end of 2010… then it was 2011… and then 2012. As the years passed and home prices continued falling, consumer spending followed, and people came to realize that any recovery in the housing market would take longer than it had after past downturns… maybe it would be five years… maybe seven, so maybe by 2014 or 2015?

As long as most people believed that what was happening had happened before they could remain grounded, go on with their lives, and await our return to national prosperity. This was the way people felt through 2009, 2010 and some part of 2011.

Last year, the news started to change and for a large segment of the population hope for recovery within a decade started to seem overly optimistic. A lost decade was now understood to be almost a certainty, and the idea of a 20-year downturn, unthinkable only a couple of years earlier, now seemed a possibility.

Of course, there will come a time when some significant number of people sans money problems walking away from their mortgages en masse, and if we continue on our current path, that time will be here soon enough.

For millions of homeowners today, their situation has deteriorated to the point that it has become close to paralyzing. Government programs have in all cases, not only been spectacular failures, they’ve also been spectacular lies. As a result people have lost both trust and confidence in those they elected as they have plainly misled and ultimately abandoned them.

Additionally, having been televised it’s now widely recognized that too many courts have been ambivalent to the flagrant forgeries and fraudulent documents banks have used in the foreclosure process. And losing faith in the courts and rule of law, is leading millions of homeowners to increasingly view their future as potentially dire.

And you know what they say: Desperate people take desperate measures. (Or is that… “Disparate people choose different pleasures. I can never remember how these sayings go… LOL.)

So, the bottom-line is that today, the issue of moral hazard as it relates to principal reductions is an entirely different matter than it was even a year or two ago. Today, and looking forward, I’m sure there is increasing reason to be concerned about homeowners being inspired to intentionally default in order to have their principal balances reduced, but the banking industry should realize that those that do so… well, if they’re willing to take that sort of risk then they’re on their way to a strategic default anyway… so, it’s really just a matter of choosing your poison.

ENTER: Mr. Dale Westhoff of Credit Suisse…

Dale Westhoff, our insipid bond analyst from Bear Stearns, says that beyond the creation of moral hazard, offering to reduce principal may also tighten lending by forcing banks to offer “price protection” to borrowers.

Now, I have no idea what “price protection” is, but I would like to say something to Dale about the idea that offering to reduce principal balances may result in tighter lending standards… so if you’ll just excuse me for a moment… be right back.

Dale? Hi there. Mandelman here. Listen, I want to be diplomatic about this… you know that pseudo-threat you made about tighter lending standards as a result of principal reductions? Did someone tell you that if you run out of rationales for not reducing principal balances, hit them with the old “banks will tighten lending” line?

Well, Dale… that would sure make for an interesting threat that I might actually care about… if banks were actually lending… or, I don’t know… maybe if anyone was interested in borrowing. However, since neither is the case, nor is it likely to be the case anytime soon, I’d say the only thing that comes to mind in response to your empty and barely veiled threat about tighter lending in the future as a result of principal reductions is… Shut the front door, Dale.

Let me share a little something with you and your banking pals… it has to do with principal reductions. Do them… don’t do them… stick them up your tailpipe… homeowners barely give a rat’s behind anymore what you do or don’t do… think or don’t think.

You see… I guess you could say that it’s wearing kind of thin, Dale my boy… and homeowners wouldn’t believe you if you said the sky was blue. Loan modifications don’t work because of their re-default rate… and now it’s principal reductions aren’t worth a darn because they create moral hazard.

Well, what would “work” for you and yours, Dale? I think I have an idea of what you and Credit Suisse are all about actually… tell me if I’m getting warm…

Just a scant couple of days ago Credit Suisse won the bidding process and as a result bought $7.014 billion in face value RMBS (“Residential Mortgage-backed Securities”) from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The New York Fed bought them from AIG and had them in their Maiden Lane II, which is the New York Fed’s… what do you call that sort of entity… shell company?

So, when Maiden Lane II bought the assets their face value was $39 billion… and they paid $20.5 billion. Now their face value is just over $7 billion and Credit Suisse paid… oh dear, wouldn’t you know it… darn the luck… the NY Fed says the actual price you guys paid won’t be disclosed until April 16, 2012.

Why is that, Dale? How about a little research on that issue? Why can’t the Fed disclose how much the Credit Suisse bid was until April 16, 2012, when the sale was made on January 19, 2012? I’m sure there’s a perfectly good reason don’t get me wrong… I’m sure it’s just something to protect the interests of us U.S. taxpayers. Always looking out for us, aren’t you Dale?

So, I hate to even mention it, but does the fact that you guys at Credit Suisse are running around like vulture investors trying to scoop up distressed residential mortgage-back backed securities at bargain basement prices bother you at all… I mean, considering that at the same time you’re publishing supposed “research” under headlines like, “Mortgage Principal Cuts Don’t Help Homeowners, Says Credit Suisse?”

The only reason I’m asking is that Laurie Goodman of Amherst Securities was quoted in that same Bloomberg article and she said…

“Amherst’s Goodman says that principal reductions are needed to avoid 8 million to 10 million more distressed-property sales.”

See, she said that because she felt it would be a bad thing to have 8-10 million more distressed property sales, but it looks like Credit Suisse wouldn’t actually mind at all if there were lots more distressed property sales, since Credit Suisse is scampering about in the night buying them for pennies on the… no, that’s not right… for some undisclosed amount to be disclosed on April 16, 2012.

The suspense is killing me, Dale. I wonder if Credit Suisse overpaid for the distressed assets they bought? Any guesses on how it will turn out?

On January 6, 2012, Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William C. Dudley, had the following to say on this very subject…

“Analysis by my staff that looks at likely borrower behavior over an extended time horizon suggests that without a significant turnaround in home prices and employment, a substantial proportion of those loans that are deeply underwater will ultimately default — absent an earned principal reduction program.”

Yeppers… so absent principal reductions, looks like I was about right once again… a whole bunch of loans are going to default… which will create a whole bunch of distressed RMBS assets for sale at pennies on the… well, at undisclosed prices for three months.

And Credit Suisse would just HATE that, right Dale? Since it’s evidently the bank’s business model at the moment. I wonder why the bank isn’t making it’s money LENDING, like banks used to do. You know, lending before all that tightening that we’re supposed to be so afraid of, according to you, if we allow principal reductions.

I’m actually thinking that you’re the moral hazard here, Dale… because you certainly don’t seem to have a moral compass. And besides, you’re statements are starting to make me dizzy.

I scanned that Bloomberg article over and over, and it must have slipped your mind because you forgot to mention the bit about Credit Suisse having bought the distressed RMBS assets from Maiden Lane II… two days before you gave the story… or rather the press release…. to Bloomberg… nicely done, Dale… very nicely done… in fact, I’d have to say crackerjack work, my slimy friend.

Don’t feel too badly about this whole thing coming out this way though… I have skills.

Oh, and one more key point… Laurie Goodman made it… it’s about the one place where principal reductions appear to be very effective in preventing defaults…

“We have shown that, even controlling for all other factors, principal reductions are more effective. Realize also that banks are doing it on their own portfolios and have been for years. Why would they continue if it was not more effective?”

Got to hand it to her there… it’s a darn fine question, isn’t it Dale? Why do you suppose banks offer principal reductions when it’s their own portfolio loans, but not when it’s the taxpayers who are on the hook, such as when the loan is owned by Fannie, Freddie, or insured by FHA?

Or, maybe the whole moral hazard thing doesn’t apply when it’s a portfolio loans on a bank’s balance sheet, is that what it is… or isn’t? Or, whatever Dale… no need to reply…no one is listening to you anymore.

Mandelman out.