Our future hinges on just ONE thing…

How the foreclosure crisis impacts our country’s standard of living from this point forward will all come down to how we handle ONE thing. We either change that one thing, or most assuredly we will at best continue to experience in the future more of what we’ve experienced to-date. It will not get better. It will only worsen and worsen significantly… unless we change the ONE thing.

A country’s “standard of living” includes such factors as income, quality employment, class disparity, poverty rate, quality and affordability of housing, gross domestic product, inflation rate, availability of education, life expectancy, infrastructure, economic and political stability and personal safety. Our country’s standard of living is what dictates our quality of life, and while money can’t buy us love, it does buy our standard of living.

There is nothing capable of destroying the wealth of our country’s 99 percent faster or more permanently that the foreclosure crisis, so there’s nothing capable of lowering the 99 percent’s standard of living more dramatically than the ongoing wave of foreclosures. Zillow’s report published in December of 2010 showed that U.S. homeowners have lost $9 trillion since the housing market’s peak in 2006, and $1.7 trillion of that total was lost in 2010 alone. And that same report showed that it’s getting worse.

- Residential property values fell by 63% more in 2010 than in 2009.

- U.S. homeowners lost $680 million in the first half of 2010, but lost $1 trillion in the second half of the year.

Evidently, the pace of the decline in residential property values is accelerating. If consumer wealth was wiped out at the same pace in 2011, we’d be just under $11 trillion in lost wealth today, but we’ve probably already passed the $11 trillion mark, because the decline in values escalated in 2011 over 2010.

So, how about for 2012… should we assume $2.5 trillion lost for the year? Based on those numbers, by the end of 2012, U.S. homeowners will have lost right around $15 trillion in accumulated equity, an amount that, at 50 years old, won’t be made up in my lifetime… and three times the amount of equity created between 2001 and 2006.

In addition, it’s important to consider that our country has had a very serious problem with income and wealth inequality for a long time, and the wealth lost due to the foreclosure crisis is making that problem exponentially worse. According to IRS data, in 1988, the average American made $33,400 adjusted for inflation, and in 2008, nothing had changed… the average American still made $33,000. Meanwhile, if you made $380,000 a year, then your income increased by 33 percent over the last 20 years. And, of course, stock market gains make the disparity much worse.

As a result, our country has one of the widest rich-poor gaps of any high-income nation today, and that gap is now growing faster than ever. Many prominent economists have warned that the widening rich-poor gap in the U.S. population is a problem that could undermine and destabilize the country’s economy and significantly reduce our standard of living.

Even Alan Greenspan, who some no doubt consider the father of our rich-poor income gap, and who is certainly no bleeding heart liberal, has said, “The income gap between the rich and the rest of the US population has become so wide, and is growing so fast, that it might eventually threaten the stability of democratic capitalism itself.” And he said that in June of 2005, imagine what he thinks today, now that the gap is widening at an inconceivable pace.

What’s old is new again…

In many ways, it’s a situation strikingly similar to what happened during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when one thing… one event… did in fact change the course of our nation.

That one thing is known as the “the Pecora Moment,” and it refers to attorney Ferdinand Pecora who, in his role as chief counsel for the United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, cross-examined the most famous men in finance as part of the committee’s inquiry into the causes of the crash of 1929.

Pecora’s questioning of Chase’s Chairman Albert Wiggin uncovered the fact that he had actually shorted Chase shares during the crash… betting against his own shareholders… and profiting from the falling prices. Pecora also revealed to the American people that National City Bank, the largest issuer of securities in the world at that time, had dished off thousands of bad loans to unsuspecting investors in Latin America and elsewhere by packaging them into opaque and complex securities. (Boy, that sure sounds familiar, doesn’t it?)

The year was 1932 and even though the country had already suffered through three terrible years of what would later that decade come to be known as the Great Depression, no one had been held responsible for what had happened. Many people blamed themselves, and some viewed the bankers as heroes because they had tried to stop the market from crashing.

You see, during the “˜Roaring 1920s,’ bankers had become America’s royalty, but when Pecora finished questioning them, the way people viewed the bankers changed dramatically. Sen. Burton Wheeler of Montana compared their acts with those of Al Capone and the American public began referring to them as “banksters.” (And here I thought we came up with that last year.)

The Pecora Moment created the political support that allowed FDR’s administration to hold Congress in session in order to pass laws that the bankers opposed, like the Securities Act of 1933, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, creation of the FDIC, Tennessee Valley Authority, et al, all of which were designed to prevent the abuses brought to light by Ferdinand Pecora. He made the cover of Time Magazine, by the way, on June 12, 1933.

Above all, Ferdinand Pecora understood the power of public outrage. And they called him, “The Hellhound of Wall Street.”

Fascinating, don’t you think? In many ways, we’ve been here before.

Today’s ONE thing…

I understand, perhaps as clearly as anyone, how complicated the financial and resulting foreclosure crisis truly is. There are a multitude of factors that have contributed to the deteriorating economic situation in which we find ourselves, but there is ONE thing… ONE factor that must be changed in order for anything else to change for the better.

Let’s understand and be very clear about what that ONE thing is:

Far too many Americans believe the “irresponsible borrower” stereotype caused the foreclosure crisis.

You know the stereotype… we all do… reckless and greedy people who bought homes they could never hope to afford by signing their names on nothing down, 80/20 “liar loans” with negative amortization and teaser rates of 1%. And the property flippers looking to make a quick buck, gambling that home values would only go up forever. They gambled and they lost and as a result today’s foreclosures are appropriate and deserved, so let’s get on with it.

(And yes, perhaps some predatory lending practices played a role too, but even those so-called victims “˜should have known better.’ After all, no one put a gun to their heads.)

As a result, instead of being seen as “saving the economy,” anything that helps homeowners is seen as a “bailout” of these homeowners, an act tantamount to rewarding their irresponsible decisions. And our policy makers become pious and smug as they “˜tut-tut’ about the “moral hazard” involved in bailing out these “irresponsible borrowers,” as if doing so would only encourage this same sort of distasteful behavior in the future.

People buying homes they could not afford is not a crisis… it’s also not something that requires further examination… it’s not something that can be… or needs to be “fixed.”

Defining the problem this way continues to prevent policy makers at both state and federal levels from taking any meaningful action to mitigate the damage being wrought by the steadily increasing numbers of foreclosures. There is never going to be political support for a “bail out of irresponsible borrowers.”

Even worse, in terms of being an explanation for the foreclosure crisis… it is just completely wrong… factually incorrect… entirely untrue. It is an erroneous belief that must be changed before anything else can change for the better… before any economic recovery can begin to take hold.

And in case you don’t think there are that many people that think this way, I only have one question: Did you watch any of the GOP presidential candidate debates? In one, the only comment made about the foreclosure crisis, was made by Mitt Romney who said, “Don’t try to sop the foreclosure process. Let it run its course and hit bottom.” And in the latest one, both Romney and Gingrich echoed the same sentiment.

Believe me when I tell you that neither Mitt nor Newt voiced that viewpoint having no idea how their audience views the foreclosure crisis. They knew they were preaching to the choir.

Of course, I do recognize that it is changing, albeit slowly. In fact, not many days pass without me hearing from another homeowner shocked that this is happening to them, as they find themselves at risk of foreclosure. And most certainly, as more people are directly affected by the foreclosure crisis, more people will come to understand it. But, that’s learning the very hardest of ways, and if we don’t accelerate that learning, we will all pay a price far beyond anything we’ve imagined.

Besides, it’s simply not true…

First of all, let’s start with the simple truth… people do not knowingly buy homes they cannot afford. No, they do not. They don’t. It’s a preposterous thought. Like telling me that there are millions of people somewhere in the USA that like to buy cars with payments they can’t afford… because I suppose they like to hide them around the block every day and night until they get repossessed. Then they wait 7-10 years until they can buy another one with payments they can’t afford so they can enjoy the experience all over again.

And homes are much worse than cars, because they cost a lot even besides the actual mortgage payments. You have to move the whole family across town… change address at Post Office … the kids get all excited… tell their friends… your spouse thinks you’re a hero. You don’t put much if anything down… maybe five or ten grand you’ve got saved… but moving in costs a fortune no matter what.

You need new furniture, and new washer and dryer… maybe a T.V. for the family room… you need garden tools, a hose, air filters, the plumber has been out twice within a month. Your wife hates the kitchen floor… you spring for tile, try installing it yourself, screw it up and end up paying twice as much to have it re-done… but now the counter tops look dingy next to the new floor… and the cabinets after that… and then, oh my God I had no idea drapes and other “window treatments” cost that much… can we have the cottage chees ceilings scraped? Sure, why not… this is our home. Patio furniture… a rose garden… of course, why didn’t I think of that?

There’s only one hitch… the payments are $3,200 a month, and you only make $3150 after taxes, and your wife stopped working last year so she could be home after school with the kids. But, hey… the house is going to keep going up in value, and besides buying one that you could have actually afforded… well, that’s no fun. You haven’t lived until you’ve raised a family in a home that’s at risk of foreclosure. Oh boy… good times!

That never happens. No, it doesn’t. And let’s just say I was to play along and say… okay, it has happened. How many times, do you suppose? Quite a few? Where… in Indiana? Massachusetts? Michigan? Lots of “irresponsible homeowners” in Michigan, were there? There’s nothing a Michigan resident likes better than going through a good old fashion foreclosure and trustee sale, is that what I’m to believe? Nonsense.

And, considering that the foreclosure crisis, as we know it today, began midway through 2006, explain to me exactly how someone who did something along the lines of what was described above managed to avoid losing his home sometime in the last FIVE YEARS? And don’t tell me it’s because of adjustable rate loans or option ARMs, because in case you haven’t noticed… interest rates have only gone down.

Stan Liebowitz is a professor of economics and director of the Center for the Analysis of Property Rights and Innovation in the management school at the University of Texas, Dallas. He’s a conservative who has written for The National Review, and I disagree with him on essentially everything.

In 2008, however, he conducted the country’s most comprehensive analysis of the U.S. housing market, studying loan level data on the 30 million mortgages in the McDash Analytics database, a division of Lender Processing Services, and his work debunked much of the conventional wisdom of the day.

The steep ascent in foreclosures began during the third quarter of 2006, and between then and the end of 2008 when his study was conducted, 4.3 million homes went into foreclosure, but his study showed that 51 percent were prime loans, not sub-prime, and although only 12 percent had negative equity at the time, they made up 47 percent of all foreclosures. Liebowitz’s study showed conclusively that negative equity, often referred to as being “underwater,” is what causes foreclosures.

Liebowitz is far from alone in his conclusions about negative equity being the primary cause of foreclosure. Once you’re underwater, the same life events that cause bankruptcy cause foreclosures… divorce, illness or injury, and job loss. Buying a home with unaffordable payments causes foreclosure about as often as a “spending sprees” cause someone to file bankruptcy. In other words, it doesn’t.

(Note: The “irresponsible borrower” stereotype has been used viciously by the financial services industry to make it much harder for people to file bankruptcy, and many people do, in fact, believe that credit card spending sprees are what cause bankruptcy.)

HUD’s Report to Congress on the Root Causes of the Foreclosure Crisis is just one of the many studies that confirmed Liebowitz’s conclusions about negative equity causing foreclosures…

The primary factor driving defaults is the value of the home relative to the value of the outstanding mortgage. HUD said most borrowers become delinquent due to a change in their financial circumstances that makes them unable to meet their monthly mortgage obligations. These so called “trigger events” most commonly include job/income loss, health problems, or divorce.

First, a trigger event reduces the borrower’s financial liquidity, and then a lack of home equity makes it impossible for the borrower to either sell their home to meet their mortgage obligation or to refinance into a mortgage that is affordable given changes in the market and in their financial circumstances.

“Rising mortgage delinquency and foreclosure rates exact a tremendous toll on individual borrowers and their communities. Foreclosures also exert downward pressure on home prices, further exacerbating problems in the housing market and the broader economy.”

Why is negative equity such a critical measure? Because it points to the likelihood of default on mortgage obligations. Equally importantly it measures the ability of the owner to sell the property; in this economy that can be especially important to get out from under an unaffordable increase in mortgage payments, be able to proactively move because of job opportunities, or a conscious need to down scale the housing cost burden that their household may no longer be able to afford because of loss of job, wages, expressions of family stress such as divorce, or in response to the ever increasing numbers of unaffordable medical bills or medical bankruptcies.

Note that no one is talking about that “irresponsible borrower” subtype, the “strategic defaulter”. People aren’t walking away from their mortgages today en masse simply because they’re underwater and now view their homes as a wealth-destroying “investment”, although that time will come soon enough if we continue on our current path. Right now we’re still only talking about people who, despite being underwater, are trying to make good on their mortgages. But life happens and when it does, they won’t be able to sell.

I think that’s enough said about what’s causing foreclosures today, so now let’s look at negative equity.

The drivers of negative equity this time around…

The quickest way to end up underwater is to live in a neighborhood that is plagued by foreclosures. … As homes go into foreclosure, they create a domino effect, lowering home values throughout a neighborhood in a cascade beyond homeowner’s control.” Anna Maries Andriotis (2009) in Smart Money

It should occur to more people, in my opinion, that we are experiencing a national decline in housing values unlike any we’ve experienced in the past.

In January of 2011, Zillow announced that its index of home values fell for the 53rd consecutive month as of November 2009, and that since June 2006, home values had fallen 26% nationwide. Zillow’s Katie Curnette pointed out, “That’s more than the 25.9 percent decline in the Depression-era years between 1928 and 1933.”

We’ve had plenty of recessions in the past. The first one was in 1819, caused by… wouldn’t you know it… banks over extending themselves. Then, between 1837 and 1843, we had a depression, and one that economists often compare to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Land speculation in the projected path of the railroads, and the failure of a large life insurance company, combined to cause that extended economic downturn.

Throughout our history, with the exception of the depression of 1837 and what went on during the 1930s, our recessions have always been short, most commonly lasting between 12-18 months, like in 1973, 1979, 1981, 1991, and even in 2000. Very few things we’ve seen in the past are capable of telling us anything useful about today or tomorrow.

The liquidity crisis of the 1930s…

A real estate bubble fueled by easy credit and reduced down payment requirements preceded the Great Depression of the 1930s. Back then, a mortgage was five years and required a 50 percent down payment, but by the mid-1920s, developers got prices to rise by stimulating demand… they started allowing people to buy with only 10 percent down. More people could put 10 percent down than fifty, so demand went up and predictably, prices followed.

All mortgages were all interest only back then, no re-payment of principal was required. The borrower was simply expected to refinance the loan when it expired in five years, most often with the same lender. (So, I guess we didn’t invent these types of loans in 2003 either. Who knew?)

Unlike what happened in 2007, the stock market crash of 1929 led to a liquidity crisis. There was no money available to borrow, so refinancing was impossible… and millions of families lost their homes to foreclosure. First, the riskier 10 percent down loans defaulted, but with no financing available, and as prices continued to fall, soon the supposedly safe 50 percent down loans went into foreclosure as well.

Consumer spending dried up so demand for essentially all goods fell, causing prices to fall… which meant companies made less money and laid people off, which caused unemployment to rise… which in turn caused more foreclosures, which lowered prices even further, thus causing unemployment to rise even further, which led to more foreclosures.

We had entered a deflationary spiral, and with home prices falling, even those consumers who could buy were reluctant to buy, and even the banks that could lend, were reluctant to lend.

As part of the New Deal, and after 33 states strictly limited or even halted foreclosures, the federal government took control of millions of mortgages and restructured them into the modern day mortgage, a loan where the principal was repaid, at first over 15 years, then over 25, and finally over 30, as we’re used to today.

Obviously, the danger of rapidly falling home prices is that, just like occurred during the 1930s, buyers sit on the sidelines expecting lower prices in the future. And lenders, afraid of the decreasing value of the collateral for the loan, increase down payment requirements, or virtually stop lending altogether, either because they can’t or they won’t. And this situation causes even further and steeper price declines, which causes homeowners to lose their equity, thus preventing them from buying other houses going forward.

In econo-speak, price declines are a self-reinforcing mechanism, or as I prefer to put it… foreclosures breed foreclosures. But this time around it was not a liquidity crisis that caused home prices to fall, this time it was very different.

The credit crisis of 2007…

In all of our past recessions, housing prices have fallen as a result of some other factor, such as liquidity drying up when a large bank or insurance company fails, or the stock market crashes, as was the case in 1929. This time however, housing prices didn’t start to fall because of something else, this time falling housing prices caused the downward spiral to begin spiraling downward.

By the summer of 2006, Fed Chief Alan Greenspan had raised interest rates 17 times in a row in an effort to cool down the housing market. Adjustable rate loans adjusted higher and those that had bought solely counting on real estate’s continued rise, and who qualified only at the low introductory rate, went into foreclosure. These were the riskiest of the loans, and the rising rates caused foreclosures to spike for the first time during the third quarter of that year.

Of course, had these loans not been packaged into mortgage-backed securities and leveraged (read: borrowed against), and then re-packed into CDOs and leveraged again… then the extent of the losses would have been minimal. But in the world of finance in 2006, where one loan for $100,000 might be the basis for $3,000,000 or more in securities and derivatives, its default had an exponential impact.

Then, a year later, in July of 2007, something happened that led to a situation we’d never seen before… S&P and Moody’s downgraded the ratings on 1,032 bonds backed by sub-prime loans, and investors all over the world lost trust in the ratings that had been placed on all mortgage-backed securities, thinking that if they had downgraded these, what about those. The result was that demand for these and related investments disappeared.

Within weeks, the credit markets were frozen solid. Central banks lowered rates and started pumping money into the system to avert a total collapse, even though only a month before the central bankers had chosen to leave interest rates unchanged.

Essentially overnight, the credit crisis made it extraordinarily difficult or even impossible for most people to get a mortgage or re-finance one, and quite predictably housing prices went into a free fall, continuing their decline ever since.

To-date, we’ve seen no meaningful private securitizations of residential mortgages since the fall of 2007. Essentially all mortgage lending today is made possible by the U.S. government through Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae and FHA.

Negative equity today impacts the housing market tomorrow…

Housing prices fell drastically between 2006 through 2009, at the same time that credit and then employment markets tightened.

In 2006, about 7 percent of United States’ homeowners owed more on a single family residential mortgage than what the property could have sold for (Calculated Risk, 2007). By 2010, estimates of those “underwater” on their home mortgage had risen to between 20 and 25 percent (Streitfield, 2010 and The Economist, 2010). And Haughwout and Okah (2009) calculate this percentage to be even larger in some metropolitan areas in the United States.

In numerous cities more than half of all homes with mortgages are underwater, including Phoenix (66.2 percent), Atlanta (58.7 percent), Riverside, California (51.4 percent), Tampa (56.5 percent) and Sacramento (50.9 percent). Other big metro areas with a high percentage of underwater homes include Miami-Fort Lauderdale (46.7 percent), Chicago (46.2 percent), Cleveland (41.5 percent) and Denver (38.5 percent).

And today, according to mortgage analyst Mark Hanson:

“Over 50% of all mortgaged households in the U.S. are effectively underwater” once implicit equity reductions are factored in. Because repeat buyers have always carried the market as the foundation, this is why demand has not come back. It’s as if half the potential buyers in America died over a two-year period of time.”

It’s also important to recognize that five years of downward slide in home prices has already caused a radical shift in opinion about home ownership. A new survey conducted by Columbus, Ohio-based Home Value Insurance Co. found that only 52 percent of Americans still consider home ownership the American dream, while 48 percent consider it more of a nightmare.

With half the mortgages already underwater, we have half the number of potential future buyers than we’re used to.

Now, imagine of the ones that are left… the ones who still have equity… and from those, deduct for those that can’t put 20% down or don’t have a 740+ FICO score. Then deduct to account for those who want to stay in their homes indefinitely, some who are worried about losing their jobs in the future… and a few more for those who don’t want to buy as long as prices are falling.

Finally, let’s talk pending foreclosures and shadow inventory. In California alone there are now two million homeowners in foreclosure. Forty percent haven’t made a payment in over two years… 70 percent haven’t made a payment in over a year… and all haven’t made a payment in at least four months. And the official shadow inventory is getting ready to top the 10 million mark.

So, when you combine the factors including the number of homes already underwater, with the changed attitudes about owning a home, the number of potential future buyers having been reduced by more than half, and the coming impact of the shadow inventory and pending foreclosures… to say nothing of what will happen should interest rates rise and the impact of the ongoing credit crisis… whatever you think your house is worth today… cut it in half at least and you may be about right.

We must stop the free fall in home prices or no economic recovery is possible…

Unlike other investments, homes are both a consumption and investment item. No other purchase or investment contributes to our economy like houses do, because we spend money to maintain and improve our homes year after year throughout our lives. Homeowners are constantly purchasing goods and services to make their homes prettier, more comfortable, safer, sounder, bigger and newer.

Yes, a home provides a family’s shelter, but it is also a forced savings account in the form of mortgage payments that pay down principal, and an investment because financial returns are realized as a home’s value rises. And homeowners have always been able to access their accumulated wealth without having to move, through home equity loans or replacing a smaller mortgage with a larger one.

Until very recently, the “wealth effect“ has always been thought of as: “The premise that when the value of stock portfolios rise investors feel more comfortable and secure about their wealth, which causes them to spend more.” Today, we can see that previous assumptions have been wrong; that “the wealth effect” is not tied to the stock market… as we’ve always been told… it’s all about the value of our homes.

When you consider that roughly 70 percent of our GDP is related to consumer spending, it’s easy to see that no economic recovery is possible unless consumers are willing to spend, and yet we are allowing the wholesale destruction of middle class wealth by continuing to allow the unabated flow of foreclosures. So, it should comes as no surprise that in August of 2011, Bloomberg reported that the consumer confidence index, which is measured monthly at the University of Michigan, fell to its lowest level since 1980.

A report by the Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) issued last January estimated that when home values change by $1,000, the owner’s consumption changes by $20 to $70… two to seven percent.

During the years 2001 to 2006, housing wealth grew by $4.8 trillion. If the CBO’s estimates for consumer spending related to home values were correct, spending should have increased by $96 billion to $336 billion. But, consumer spending during that period rose by $2.17 TRILLION, so the wealth effect from housing obviously accounts for quite a bit more than the CBO had thought.

Much of the reason for this is that when someone purchases a home the equity in that home creates an economic safety net going forward. That safety net allows for less money to be saved for retirement, because the certainty of owning a home in one’s old age means less money will be needed in the future for housing expenses, so spending is increased by the certainty of equity and home ownership in their future.

The simple fact is that owning a home, in addition to Social Security and whatever pensions and/or private savings may be present, has always been America’s retirement plan. Destroy our largest source of future wealth and we will curtail our spending, simple as that.

Barry Ritholtz, in November of 2010, also weighed in on the idea that the wealth effect is tied to stock market performance, in his article titled: Wealth Effect Rumors Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.

It is taken for granted that a rising stock market stimulates the animal spirits, sending consumers off shopping.

The basic premise of the wealth effect is well known: As the value of stock portfolios rise during bull markets, investors enjoy a feeling of euphoria. This psychological state makes them feel more comfortable “” about their wealth, about debt, and most of all, about spending and indulgences. The net result, goes the argument, is that consumers spend more, stimulate the economy, thus leading to more jobs and tax revenues. A virtuous cycle is created.

The problem is, the theory is mostly nonsense.

The vast majority of Americans have a rather modest sum of cash tied up in equities. 401ks, IRAs, investment accounts “” these are primarily the province of the well off. Ownership of equities is heavily concentrated in the hands of the wealthiest Americans. Start with the top 1%: They own about 38% of the stocks (by value) in the US. The next 19% owns almost 53%.

That leaves the remaining 80% of American families with less than 10% stake in the stock market (See Federal Reserve’s Z.1 Flow of Funds report for the most recent info).

How is THAT going to cause a wealth effect? Especially when you consider the median family’s stock portfolio is worth well under $50k. These are the millions of families who are the principle consumers of cars, food, clothing, electronics, energy, health care, etc. To them, a rising stock market is nearly meaningless.

The biggest investment for the typical American household remains their home, with a median value of ~ $200k. Put 20% down, and you see a 10 to 1 leverage. The impact of Real Estate on any wealth effect is much greater than the stock market.

Additionally, in a recent New York Times article titled, Gloom Grips Consumers, and it May Be Home Prices, the newspaper pointed out how conventional wisdom related to the wealth effect is changing…

That has led a growing number of economists to argue that the collapse of housing prices, a defining feature of this downturn, is also a critical and underappreciated impediment to recovery. Americans have lost a vast amount of wealth, and they have lost faith in housing as an investment. They lack money, and they lack the confidence that they will have more money tomorrow.

“People don’t expect their home to regain value, and that’s really led to a change in consumer attitudes about the economy that we’ve just never seen before,” said Richard Curtin, a professor of economics at the University of Michigan who directs its Survey of Consumers.

Economists have only recently devoted serious study to how a decline in housing prices affects consumer spending, not least because this is the first decline in the average price of an American home since the Great Depression.

And yet, even in the face of such overwhelming evidence that the wealth effect is not tied to stock market gains… Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, writing an op-ed column for The Washington Post on November 5, 2010, titled, Aiding the Economy: What the Fed Did and Why, demonstrated that his beliefs about the wealth effect are wrong…

… higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.

So, it should come as no surprise whatsoever that Bernanke’s quantitative easing and myriad of other lending and spending programs, while they have propped up the stock market and allowed the rich to get richer still, they have had little or no impact on the real economy.

And economist Dean Baker, in his 2010 paper on the Impact of the Housing Crash of the Wealth of Baby Boomers, has the following to say…

“The collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting plunge in the stock market destroyed more than $10 trillion in household wealth. The impact was especially severe for the baby boom cohorts who are at or near retirement age. Using data from the Federal Reserve Board’s 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances to compare the wealth of baby boomers just before the crash with projections of household wealth following the crash, projections show that most baby boomers will be almost entirely dependent on their Social Security income after they stop working.”

The words of Hernando de Soto on today’s economic crisis…

Consider the words of one of the world’s leading economists, Hernando de Soto who has been hailed as an innovator who could help reinvent the future of the global economy. He is the author of “The Other Path” and “The Mystery of Capital,” is the director of Peru’s Institute for Liberty and Democracy and a champion of market economics and property rights.

The following has been excerpted from an interview with Hernando de Soto on Radio Free Europe on October 28, 2011… “Recession is a Matter of Knowledge.”

If the real problem was the contraction of credit due to lack of money, then the huge injection of legal tender via quantitative easing and bailouts, and financial rescue packages…should have spurred the economy.

It’s been four years since 2007 and none of the usual recession remedies have actually worked. This is because people are simply not lending. And why are they not lending? Because nobody really knows who is broke, who is a risk, and where the opportunities are.

When credit contracts, which is what is happening in the West today — private credit contraction — the result of that is, of course, less investment, less credit, which means less production, which means more unemployment, which means the fall of prices of things, which means the loss of confidence.

And then you go back to complete the vicious circle, which makes credit contract even more as a result of less there is less enterprise, less employment, etc. That’s the vicious circle we are in.

Whether you are looking at records of derivatives, whether you are looking at balance sheets, whether you are looking at any accounting that has to do with fair market prices — in other words, reflecting what the value of your goods is according to what price they can fetch on the street instead of what you yourself may consider would be a just price — we really are flying blind.

And that blindness is what is stopping people from believing each other because credit comes from credibility. The reason is basically an enormous collapse of confidence, which will not reappear until the books start saying what people really have in their pockets.

What the West is afraid of is that there will be a run on the banks.

Why don’t they change it? And my reply to that is that at this time, they are so afraid that if they do give the knowledge it will be obvious in a matter of days which banks can’t pay their debts. And then, what the West is afraid of is that there will be a run on the banks. That’s why, when this crisis first came on, many people said, “Well, let’s find a way of telling the public that those who have savings in the bank will be protected — through insurance or whatever it is — so that everybody understands that they are in safe hands.”

We can expect political turmoil. There is no way that you can bring down the incomes and the welfare of millions of people throughout the world without you getting severe protests.

So we are obviously going to go through very big political transformations and we are going to have to make terrible adjustments until we are able to get back to reality. And always this has political consequence. And that is why it is so important that we make the corrections as soon as possible and that politicians with courage are able to tell us how we can make those corrections without blaming the neighboring countries for having done all the harm. Otherwise, like in the 1930s, we are going to open the whole situation to conflicts, social wars, and transnational wars.

I think that there is no way that you are going to avoid a collapse. The question is, are you going to be able to do it with a soft landing with governments in control, or whether it is going to be a hard landing.

In terms of whether we can survive with the existing system with just a little bit of quantitative easing, with just a little bit of bailout and rescue packages — that, I am convinced, will not work.

The English language may be Hernando de Soto’s second, but I just can’t imagine anyone saying what needs to be said any clearer than that. So… Amen to that, Mr. Hernando de Soto.

The cost of foreclosures to our society…

It shouldn’t be difficult to imagine that the foreclosure crisis is having a devastating effect on our society monetarily and otherwise, however, until recently it was difficult to quantify these effects, beyond lost equity, in monetary terms. We all need to recognize that the unacknowledged victims of the foreclosure crisis are those who haven’t lost homes to foreclosure, but nonetheless are paying the price that foreclosures impose on all of our communities.

The Massachusetts Alliance Against Predatory Lending (“MAAPL”) and the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau published a report in June of 2011, titled: “VACANT SPACES ““ The External Costs of Foreclosure-related Vacancies in Boston.” The report presented findings from a comprehensive and very well documented study of only three specifically quantifiable costs paid by the public-at-large that result from foreclosure-related vacancies in the City of Boston:

- The costs of securing vacant homes.

- The costs associated with the increased crime caused by vacant homes.

- The drop in property values and property tax revenues for whole neighborhoods when a nearby house goes vacant.

The Vacant Spaces study concluded that, “a single foreclosure costs Boston and its citizens somewhere between $157,058 and $1,028,862.”

When you break it down, here’s what it looks like for the citizens of Boston:

- Taxpayers lose $20,723 to $32,053 per vacancy (Based on a 22 percent reduction in value when sold after foreclosure.)

- Crime victims lose $12,813.

- Criminal investigations, trials and incarcerations cost $16,316

- Homeowners lose equity totaling $157,058 to $1,028,862.

And this is in addition to the costs to families losing homes to foreclosure. The study showed that if every one of the 821 foreclosure deeds filed in the City of Boston last year created a vacancy, the cost to the city would have been $844,695,702… almost a billion dollars. Unquestionably, the foreclosure crisis’ impacts are many and varied reaching far beyond the lives of those losing homes.

The “Vacant Spaces” report concludes by saying the following:

This decrease is multiplied by vacant properties’ impact in terms of appearance, health issues, increased crime, potential of fire, loss to the fabric of the community by instability, the loss of the families to the fabric of community institutions and schools. The loss in property values then contributes to the negative equity of surrounding homes and people’s inability to sell and move from homes now underwater when they need to for economic reasons. Fold in the stress and specter of homelessness and need to move, the initial foreclosure can cost residents their jobs and health.

This collateral damage impacts local spending, the local economy, small businesses, and jobs. Additionally, the loss of property values and primary tax base becomes a body blow to municipal governments and services. Perhaps equally or more importantly, services and finances of municipal governments are taxed as they try to manage foreclosed, usually ignored and frequently vacated, properties.

These strain inspectional services and increase negative health consequences, issues of upkeep and appearance of properties and degradation of vacated properties. Vacancies in turn lead not only to property related crimes, but significantly increase violent crime, the dangers of fire and such health hazards as vermin, mold and mildew, and neglected pools that breed mosquito populations.

This crisis impacts the entire economy, the revenues and costs to all levels of our governments and ultimately all of us as taxpayers and participants in an economy we need to recover.

Another report prepared for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts shows government forecasts have been 100 percent wrong…

A subsequent MAAPL report, published in October of 2011, and titled: “Foreclosures: Denying Massachusetts an Economic Recovery,” went even further by showing that the Congressional Budget Office’s (“CBO”) forecasts of the fiscal impact of foreclosures on the State of Massachusetts, have all been wrong by a factor of 100 percent. The actual numbers have consistently come in twice as high as the CBO’s forecasts.

A CBO report published in 2007, forecasted that the loss in Massachusetts’ property values would be about 7.88% between 2007 and 2009. But, a study by the Warren Group in 2011 showed that the actual property value loss in Massachusetts was roughly 20%. And that means estimates of the multiplier impacts on household spending were significantly underestimated, as well.

As stated in MAAPL’s October report:

The figure from the CBO’s report, Housing Wealth had come out to a loss of about $2B per month from our state economy. Multiplied by what may yet turn-out to have been a conservative coefficient, our new figures using the actual loss in property values of about 20% puts that figure at slightly over $4B per month from our overall state economy. That is the loss of spending by regular people whose spending drives 70% of our economy.

These two studies together show that the devastating impact on our economy is far beyond what gets captured by looking at simple job losses and implies that going forward we should not be overly conservative about the ongoing impact of the foreclosure crisis.

Why the forecasts were so terribly wrong…

MAAPL’s October report also explained why forecasts have been proven so incredibly inaccurate.

Most of the research available to look at the impact of the foreclosure crisis was done early in, or even before this foreclosure crisis became full-blown. It measured the impact of what we would now consider occasional foreclosures, or reached all the way back to the more limited foreclosure crisis of the early 1990s.

The statistics that these reports were based on show a gross underestimate of the real impact of the foreclosure crisis.

In addition, the interactive impact of all of these negative financial and social effects was not apparent when the number of foreclosures was smaller. In updating research for our Commonwealth, there is also the potential, even though we are now inserting the actual figures for property loss, for instance, that we are still yielding an underestimate of the actual impacts of the foreclosure crisis; the multipliers before the worst of the crisis may also have been too small.

Now recognized as underestimates, the statistics from those early studies were already so large and predicting such devastation that they were hard for policy makers to swallow.

Yet if we have learned anything from the last few years it is that our tendency to want to make very conservative estimates and shy away from the potential far-reaching impacts of the foreclosure crisis has not helped us. In fact, underestimates may have hurt our ability to act at the policy level in a timely way to even ameliorate the worst harms from this foreclosure crisis.

A stereotype being reinforced by those who benefit from blaming borrowers…

The idea that foreclosures are the result of people having bought homes they could not afford has its natural roots in two places. The first was the result of a certain kind of jealousy that many who did not buy homes during the bubble had started to feel by 2005 as they drove around their neighborhoods seeing newer and bigger homes going up all around them. Their inner voices had started to wonder how it was that they had apparently fallen so far behind their peers.

When the bubble started to deflate in 2006, many started to feel that they had missed the train that had now left the station, and they questioned themselves… had they been too risk averse?

A year and a half later, however, the credit markets had frozen and the free fall in housing prices had begun in earnest… with the number of foreclosures now making national news… the media called it a “sub-prime crisis,” one caused by “irresponsible sub-prime borrowers,” and those that had questioned their own decisions not to buy or borrow during the bubble found easy vindication.

“Ah ha!” they said to themselves. “It wasn’t me after all. I didn’t fall behind after all. I was actually prudent… smarter… more responsible than the others. Well, they made their bed, now they must be punished and lose those homes.”

This group of people were quite happy that home prices were now falling, with the clear implication being that when prices fell far enough, they would be able to swoop down from their perches of responsibility and buy up all the bargains… and then they would be the rich ones, they would reap the rewards of their superior decision making during the bubble… Bwhahahahaha!

These people didn’t consider that when the water goes down in the harbor, so do all the boats.

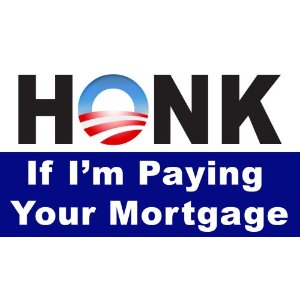

The most famous person from this group became so well known only after he shouted from the trading floor at the Chicago Board of Trade…

“This is America! How many of you people want to pay for your neighbor’s mortgage that has an extra bathroom and can’t pay their bills? Raise their hand.” The traders around him began booing loudly. “President Obama, are you listening?”

Do you remember who that was? It was CNBC’s Rick Santelli… the man who started the Tea Party movement in this country by decrying government bailouts, and branding homeowners who were struggling financially, “losers.” In an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times, Santelli called his televised and highly emotional rant, “the best five minutes of my life.”

There’s another factor that makes the “irresponsible homeowner” stereotype so easy for those not yet affected by the foreclosure crisis to accept. It’s a cognitive bias, meaning it affects how we’re predisposed to think, and behavioral economists would refer to it as “the just world hypothesis.”

You see, especially in this country, we all very much want to believe that we live in a just and fair world… it makes us feel relatively safe. As a result, when we see something bad happen to someone else, we look to believe that they did something to deserve or at least cause their misfortune to occur.

For example, when someone tells us about someone diagnosed with cancer, we’re prone to ask whether they were smokers, or whether they were healthy eaters, or whether they were overweight or exercised enough, or whether cancer runs in their family. We’re trying to attribute the cancer to something about the person or what the person did to the the diagnosis. If we can’t make such a connection, we may still believe there must have been something that caused it to happen. In simple terms, random hardships are scary.

It follows, therefore, that when we hear of people losing homes to foreclosure, we want to believe that they did something to make such a thing happen. And so when we hear someone on television say that they borrowed irresponsibly, we accept it without questioning whether it makes sense, because we want it to be the case.

Perpetuation of the stereotype is no accident…

Why is it that certain individuals are trying to spin the story of the financial and foreclosure crises? Barry Ritholtz, writing in the Washington Post for Bloomberg on November 5, 2011, offers the following explanation in an article titled, “The Big Lie Goes Viral.”

“Some are simply trying to save face. Interest groups who advocate for deregulation of the finance sector would prefer that deregulation not receive any blame for the crisis. Some stand to profit from the status quo: Banks present a systemic risk to the economy, and reducing that risk by lowering their leverage and increasing capital requirements also lowers profitability. Others are hired guns, doing the bidding of bosses on Wall Street.”

So, the ongoing perpetuation of the “irresponsible borrower” stereotype is not accidental, it’s a coordinated and highly sophisticated communications initiative being implemented by motivated experts.

The homeowner side of the fight, on the other hand, is comprised of individual homeowners and a relative handful of attorneys, each engaged in individual battles to save their own homes… along with a growing number of journalists and independent bloggers who appear to be sharing the same audience.

On the homeowner side of the fight, nothing is organized. And as a result, the stereotype of the “irresponsible homeowner” remains safely ingrained, and with over 3,000 homeowners being evicted every single day, 365 days a year, homeowners are losing the war.

It’s true that in the past year, more court decisions are favoring homeowners, but 3,000 people being evicted as the result of a foreclosure every single day of the year means the banks are still securely driving the foreclosure bus, and they’re not nearly as worried about a decision in Massachusetts or Ohio as some would like to think.

Santelli’s rant in the Oval Office…

Here’s what President Obama said just a month after his inauguration during his speech on February 18, 2009, introducing his Making Home Affordable plan, which was to save roughly 8 million homes from foreclosure through a combination of refinancing and loan modification.

But by making these investments in foreclosure prevention today, we will save ourselves the costs of foreclosure tomorrow ““ costs that are borne not just by families with troubled loans, but by their neighbors and communities and by our economy as a whole.

President Obama (2009) introducing his Making Home Affordable Plan

However, recently Ezra Klein wrote two articles for the Washington Post after having interviewed Obama Administration insiders, and he explained how Rick Santelli’s ill-conceived and insensitive rant spread so far that it actually exerted influence in the Oval Office. Among the many important insights Klein gleaned from his interviews, as to why the administration didn’t do more to stop foreclosures he said…

“On first blush, there are few groups more sympathetic than underwater homeowners or foreclosed families. They remain so until about two seconds after their neighbors are asked to pay their mortgages. Recall that Rick Santelli’s famous CNBC rant wasn’t about big government or high taxes or creeping socialism. It was about a modest program the White House was proposing to help certain homeowners restructure their mortgages. It had Santelli screaming bloody murder.”

“Ultimately, concerns about the politics and policy questions behind widespread debt forgiveness were sufficient to scare the administration off of the policy.

Klein also quoted White House labor economist Jared Bernstein…

“Moral hazard is a big problem when you’re making policy regarding write-offs and principal cramdowns. It was always in the room when you were trying to help one underwater homeowner write off some debt while the person next door was playing by the rules and paying their mortgage every month. But with hindsight, I might have argued more rigorously against the risk of it.”

Klein also says the following about the administration’s handling of the housing crisis…

“The Obama Administration has mishandled the foreclosure crisis badly, and members of the administration both know it, and regret it.”

They may very well regret it, but obviously the degree of regret they’re experiencing has not yet risen to the level that they feel compelled to do anything to change it.

We need to shatter the “irresponsible homeowner” stereotype in order to protect our standard of living…

Throughout much of the last century, movies portrayed African-Americans as being unintelligent, lazy, or violence-prone. These stereotyped images encouraged prejudice against African-Americans throughout our society, which led to widespread discriminatory practices and the continuation of “Jim Crow“ laws in the South for decades longer than might have otherwise been the case.

Even today, many studies still indicate that African-Americans convicted of first-degree murder have a significantly higher probability of receiving the death penalty than do whites convicted of the same offense.

And African-Americans in this country still face discrimination in housing, employment, and education, are still victimized by insurance red-lining, and terrorized by white supremacists who maintain that their own race is superior to all others.

Stereotypes can be immeasurably destructive…

We develop stereotypes when we are unable or unwilling to obtain all of the information we need to make fair judgments and accurate assessments about people or situations. When stereotypes are unfavorable they often lead to unfair treatment, discrimination and persecution.

Quite often, we have stereotypes about people who are members of groups with which we have not had any firsthand contact. And, sometimes stereotypes develop when the isolated behaviors of a small number of people in a group are viewed as representing the behaviors of all members of that group.

Such is the case with today’s stereotypical “irresponsible borrower.”

Scapegoating is the practice of blaming a group for the failure of others. It is not uncommon that a group is blamed for the mistakes or crimes of others, especially when the blame is being placed on a group unable or unwilling to defend themselves against the charges.

Minorities are often the targets of scapegoating, and today’s homeowner in financial distress, as minorities go, makes for an easy target. Those in the majority are more easily convinced about the negative characteristics of a minority with which they have no direct contact, and homeowners at risk of foreclosure live in a sort of self-imposed isolation, bound by shame and fear, and capable of vacillating between unreserved sadness and unqualified rage.

Quite often, they tell no one of their situation, quietly enduring inconceivable stress for years, in some cases, and ending up afraid to answer the phone or even go outside, in the most extreme examples. Some have described their time spent at risk of foreclosure as being akin to spending that time in solitary confinement.

When a minority is blamed for some social ill, violence, persecution, and in the most extreme examples, genocide can result. In our history, unemployment, inflation, food shortages, disease, and crime in the streets are all examples of social ills that have been blamed on scapegoats comprised of various minority groups.

Today’s stereotypical “irresponsible borrower” is being made into the scapegoat for the financial and foreclosure crises.

Demagogues exploit latent beliefs, fears, emotions, vanities and expectations of the public to achieve their own political objectives. They depend upon propaganda and disinformation.

Most demagogues achieve their success because people want to believe that there is a simple cause of their problems. Through the use of propaganda, persuasive arguments are made that one group is to blame for problems being faced by the majority.

Wall Street’s bankers are today’s demagogues…

However, as a population becomes more educated, it becomes much more difficult to sway public opinion with propaganda, and in a society where access to information is not restricted, it is ultimately impossible for demagoguery to sustain itself for very long.

Revisionist history, brought to you by the American Bankers Association…

In 2009, Edward L. Yingling, the President and Chief Executive Officer of the American Bankers Association, testified in Congress related to the then proposed Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. I wrote about it at the time, including quoting from Mr. Yingling’s testimony as follows:

“It is now widely understood that the current economic situation originated primarily in the largely unregulated non-bank sector. Banks watched as mortgage brokers and others made loans to consumers that a good banker just would not make and they now face the prospect of another burdensome layer of regulation aimed primarily at their less-regulated or unregulated competitors. It is simply unfair to inflict another burden on these banks that had nothing to do with the problems that were created.”

Yes, you read that correctly, he said that the banks had nothing to do with the problems that are generally referred to as the worst financial and economic meltdown since the 1930s. The bankers had nothing to do with what happened that brought an end to Wall Street’s investment banks. The cause of our economic calamity, to listen to the financial services industry, was primarily irresponsible borrowing with a side order of unethical mortgage brokers. The bankers were entirely uninvolved… victims of the crisis, more than anything else.

Lest you think that I am overstating the situation, consider what Bethany McLean, the financial reporter that broke the ENRON story, and more recently the co-author along with Joe Nocera of the book on the financial crisis, “All the Devils Are Here,” had to say when she appeared on PBS’ NOW with David Brancaccio to talk about the attitudes on Wall Street.

“I think there is still the attitude that it is the fault of American borrowers for borrowing beyond their means, for homeowners for moving into homes they couldn’t afford, and all Wall Street did was package this stuff up and sell it to investors around the world… that they are the least of the villains, rather than the greatest of the villains.”

The problems with this version of the story is that if I’m to believe that the bankers had nothing to do with causing the crisis, then I also have to believe that they made literally hundreds of billions of dollars completely by accident. I mean, the bankers did awfully well by any standard over the last few years, but if they didn’t have anything to do with what happened, then they did incomprehensibly well… I mean like single ticket holder in the Powerball lottery 10 days in a row type well.

The bankers had nothing to do with it… like as if Lloyd Blankfein over at Goldman Sachs looked at his computer screen one day and sais, “Sonofabitch, will you look at what’s going on here… who would have ever thought this would happen… Woohoo… we’re rich betches!” And then he went dancing around Goldman’s headquarters kissing everyone, male and female, on the mouth. The bankers had nothing to do with it… sell it somewhere else…

The banking industry public relations machine gave us the myth of the “irresponsible sub-prime borrower.” It never was a “sub-prime” crisis, if you recall earlier in this article, Professor Liebowitz’s study of 30 million mortgages in 2009 showed that 51 percent of foreclosures were prime loans, not sub-prime.

But, we are allowing the post-crisis story to be told almost entirely by those responsible for the crisis. And as long as we allow this to go on, the “irresponsible borrower” stereotype will remain alive in the minds of tens of millions of Americans, our politicians will lack the political support to do anything to mitigate the damage being wrought by foreclosures, our economy will continue to ratchet down year after year for perhaps decades… and the standard of living of our children will have will be nothing like ours.

And that’s capable of bringing me close to tears if I think about it too long, until I start to get really mad, and then all I can think about is kicking the crap out of Rick Santelli in a Chicago parking lot on national television. (And if you don’t think I’d do it, given the opportunity, then you don’t know me at all.)

We need to get organized, at least around this one thing…

Already, our nation’s official poverty rate in 2010 was 15.1 percent… up from 14.3 percent in 2009, which was the third consecutive annual increase. And in 2010, there were 46.2 million people in poverty, up from 43.6 million in 2009, which was the fourth consecutive annual increase and the largest number in the 52 years for which poverty estimates have been published.

How much longer do you want to wait before we get organized and do something about shattering this stereotype that is causing unconscionable suffering and preventing a national catastrophe from being addressed?

Susan Wachter, professor of real estate at the University of Pennsylvania, fears that foreclosures and tight credit could send home prices falling to the point that millions of families and thousands of banks are thrust into insolvency.

“Homes are different than other goods and services,” she says. “The fragility of our banking system is tied to the value of homes. If we have another 20% decline in prices, we’ll need another bailout of banks similar to what we just did,” Wachter says.

Another banking bailout? Well, that certainly sounds like the end of the world to me.

Economist Dean Baker, at the Center for Economic Policy Research in Washington, D.C. says that, “If housing prices don’t stabilize, financial troubles could spread everywhere “” to credit cards, car loans and commercial mortgages. The waves of bad debt will just keep coming. An out-of-control price collapse would have dire consequences.”

Baker wants the U.S. government to take aggressive steps to help underwater homeowners, not just financial institutions. He supports the significant expansion of programs that restructure troubled mortgages.

According to Baker…

“We have more than 25 million people unemployed, underemployed or who have given up looking for work altogether in this country. One might think that Congress would convene a supercommittee to get people back to work rather than figuring out a way to undermine programs that people need, but it’s the 1 percent that pay for elections, not the 25 million workers suffering from their greed and incompetence.”

“Politicians pushing right-wing positions in public debate now operate with the assumption that they can get away with saying anything without getting serious scrutiny from the media. That is why right-wing politicians repeatedly blame government regulation for the failure of the economy to generate jobs. Even though there is no truth whatsoever to the claim, right-wing politicians know that the media will treat their nonsense respectfully in news coverage.”

So, here’s what Abigail Field and I need from you…

Homeowners… I know you’re stressed and busy and overwhelmed. And I know you don’t know what’s going to happen next and if you’re not scared to death these days, then you’re not breathing. But you have to do more.

At the very least, we when you see an article that’s intended to shatter the stereotype of the “irresponsible borrower,” like this one for example… don’t just read it… forward it to people you know that aren’t at risk of foreclosure. Post it on your Facebook page… email it to your congressional representative… If you’re a member of an online group, post it there too… for God’s sake, drop copies of it from your helicopter, if you have a helicopter. Help spread the message far and wide.

Bloggers… We don’t compete with each other, Abigail and I write articles, we don’t sell advertising, so cross post this article and ask your readers to send it to everyone they know. And get in touch, because we’re building a list of “thought leaders” and we need your name and contact information on that list.

That way, when we produce an article or research report intended to address the “irresponsible borrower” stereotype, we can email it to you so you know to post it. We need to get this one message out as far and wide as possible.

Lawyers and other industry professionals… You have Websites and blogs, but more importantly you have clients you talk to everyday that are a part of this fight. I know how busy you are, but I need you to spend the extra 10 minutes it takes to not only post this and other articles to come, but to tell your clients about what we’re doing over here… tell them to read it on Mandelman Matters or on your site, or anywhere else for that matter.

It’s all going to come down to how we handle ONE thing… the “irresponsible borrower” stereotype. Oh, I know it’s going to change eventually, but we can’t wait until eventually… we need to do it this coming year… a year that politicians are paying attention.

Because otherwise, and this much should be clear to all of us… we will lose… and lose BIG… and the truth of the matter is that WE… the people… WE’RE TOO BIG TO FAIL!

Thanks for reading me… whew, that was exhausting…

Mandelman out.

Subscribe to Mandelman Matters