Mandelman U. Presents: There�s Credit Default Swaps & then there’s Credit Default Swaps

Complexity We Eschew at Good Old…

Mandelman U.

Sit, Sulte, Simplex

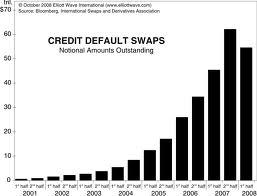

In 1998, there were so few Credit Default Swaps in play that they were hardly worth counting. Not only were there a relatively small number of these credit derivatives being issued, but they essentially never paid off. That’s right. Issuing credit default swaps, at least as they were originally conceived and utilized, was risky like issuing flight insurance was risky.

So, what the heck happened to elevate credit default swaps to the status of global economy killer as they might rightfully be described today? Well, there are credit default swaps… and then there are credit default swaps.

The Set-Up…

Let’s start with this fact: banks are required to hold funds in reserve for future losses, and the amounts they reserve can not be invested to maximize return, so they want to hold as little in reserve as is permitted by what are called Basel II regulations. How much a bank is required to hold in reserve depends on what type of assets… read: loans… are on its balance sheets. The riskier the loans a bank owns, the more capital the bank must keep in reserve. But, additionally, riskier loans pay better.

If a bank has invested in a bunch of sub-prime mortgages, they have to reserve for some percentage of homeowners who default on their payments and/or pre-pay their mortgages, but if those mortgages are inside a triple A rated security, and if that security is “insured” by a credit default swap, then they don’t have to reserve anything for a future loss, because it doesn’t appear that there will be a future loss. Oh, and if the whole transaction can be handled off the bank’s balance sheet in the first place, such as inside an SIV or Special Investment Vehicle, that’s held off-shore… then so much the better.

How it all began…

Sometime in 1994, JPMorgan created the first credit default swap.

It seems that JPMorgan had provided Exxon with a $4.8 billion credit line, but Exxon was now facing $5 billion in punitive damages as a result of the Valdez catastrophe, so JPMorgan was required to reserve the funds for such a credit risk. To clean up their balance sheet, JPMorgan sold the credit risk involved in the Exxon credit line to a large European banking concern, and thereby reduced the amounts it was required to hold in reserve. It swapped the risk of $4.8 billion in extended credit defaulting.

It worked so well that, in 1997, JPMorgan created BISTRO, which stood for “Broad Index Securitized Trust Offering.” BISTRO was a proprietary product for JPMorgan that used CDSs to clean up a bank’s balance sheet, just like the bank had done for itself in the case of Exxon a few years back.

But, BISTRO actually used the securitization process to break up the credit risk into smaller pieces, which allowed smaller investors to get in the game… not everyone can take on a $4.8 billion risk… and in that sense BISTRO was the first “synthetic collateralized debt obligation” or synthetic CDO.

Don’t be discouraged if you’re not getting all that at the moment, hopefully I’ll straighten it all out in a minute or two.

Then, in 2003, best I can tell, Goldman Sachs convinced AIG to offer a credit default swap on a CDO… a collateralized debt obligation. You can think of a CDO as being a derivative of a mortgage-backed security.

Remember how we create mortgage-backed securities? We take a bunch of mortgages and put them into a pool and then we create a contract that prioritizes the payment streams into slices called tranches. The top is the safest tranche, it pays the lowest interest rate and is always rated triple A because it receives its payments before any other tranche. The middle tranche, called the mezzanine or “the mez,” if you’re that Wall-Street-cool, gets its payments after the top tranche has been filled, and it is rated BBB. The bottom tranche doesn’t get a nickel until the top two have been filled as expected, and it is often unrated, or in other words is like a junk bond. It offers the highest rate of interest, but also carries the greatest amount of risk.

Okay… still with me, right? If that last paragraph was confusing, you should probably go back and read another Mandelman U. article: Securitization and Mortgage-Backed Securities, which explains the securitization process and mortgage-backed securities thoroughly and in simple terms.

So, let’s say that we’ve sold all the triple A rated tranches and we’ve got a bunch of BBB rated stuff laying around. Well, if we… let’s call it… re-securitize all of the BBB tranches, we’ll end up with another top tranche that will again be rated triple A, another “mez” rated BBB, and another unrated bottom tranche. But notice that the first time we securitized the mortgages the payment streams that went into the tranches came directly from the mortgages in the pool. But this time, we re-securitized the BBB tranches from other securitizations, so we’re one step removed as compared with the first time around.

This time, for our triple A rated tranche to get a nickel, the top tranches in the first securitizations have to have been filled up with payment streams as expected. So, a CDO’s income isn’t based on payment streams from mortgages, rather it’s income is based on payment streams from securities whose incomes are based on mortgages.

So, Goldman Sachs convinces AIG to offer credit default swaps on triple A rated tranches of CDOs. I mean, why not? After all, the historical loss rates on American mortgages were damn near zero. And, thus was reborn the credit default swap… now tailor made for the mortgage boom that was fast bringing the U.S. economy out of the recession created by the bursting of the dot-com bubble a few years before.

Now, investors buy CDOs, which look great, because they are based on BBB rated tranches, so they pay higher interest than were it based on the triple A rated tranche, BUT… it’s re-securitized, if you will, so it has a new triple A rated tranche itself. And you can get a CDS so there’s no risk at all… load ‘em up. They look as safe as U.S. Treasury bonds, but they pay much higher interest rates, and have no risk of default as a result of the inexpensive CDS you added on top.

Oh, and these CDOs are hard to construct and value, so Wall Street investment bankers can make a bundle putting the deals together and selling them all over the world. In fact, almost no one on the planet can truly understand what they’re made up of, and what they’re worth… absolute heaven for Wall Street types.

(You see, it’s important to understand that the harder it is to value something, the more a Wall Street investment bank can charge to put the deal together and make a market for whatever it is. Just think of it as being the opposite of gold. Gold is a commodity that trades all over the world, so all you need to do is look up the price of gold today and there it is for all to see. So, Wall Street firms aren’t much interested in selling gold… too easy to price, get it?)

The most simplified example of a credit default swap would be issued as related to highly rated corporate bonds. Let’s say your Aunt passed away and left you $100,000. And you decided to put that $100,000 into a triple A rated Exxon-Mobil corporate bond, perhaps instead of a Treasury bill of some sort, because Exxon-Mobil was offering a slightly higher interest rate and since Exxon-Mobil is one of the world’s largest and most stable corporations, you saw the investment as being just about as safe as bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury.

But, just in case… because you didn’t want any risk whatsoever, you decided to buy a credit default swap, which in essence insured the investment you made in the Exxon-Mobil bond. If Exxon-Mobil defaulted on their obligation to pay you as promised, the company who issued the credit default swap would pay you what you were owed under the terms of the bond.

Of course, triple A rated corporate bonds, like those that might be issued by Exxon-Mobil, very rarely default… and by very rarely, I mean like never, so you probably wouldn’t need to insure against such an event, but that’s also why doing so wouldn’t be very expensive… very much like the flight insurance that you can buy before boarding a given flight.

The odds of that individual flight crashing and you being killed as a result are remote… very remote1. So, if you’ll pay something like $50, some insurance company will pay $1,000,000 if your flight crashes and you die as a result. A credit default swap issued on a triple A rated Exxon-Mobil corporate bond might be considered about that risky, and therefore it wouldn’t cost very much to buy.

For example, Michael Lewis, in his book “The Big Short,” quotes the cost of a credit default swap on a $100 million mortgage-backed security as being $200,000 a year for ten years. So, if you paid the annual premium for the entire ten years, you would have paid 2% of the insured amount. Two million to get you One hundred million… that’s 50:1… better than the odds when playing roulette.

Of course, you might not have paid for ten years before your bond or mortgage-backed security defaulted, so in that case your return would have been much greater. Like if you owned the credit default swap for one year, and as a result had only paid one $200,000 premium payment, then your return would be 500:1, right? Not too shabby, if you can get in on something like that, I’m sure you’d agree.

I’m not saying that’s exactly how today’s credit default swaps work because for one thing, they are only offered to institutional investors, and not on the bond you bought with money your Aunt bequeathed to you. But, as descriptions go, it’s not that far away either, so hopefully you’re getting the general idea.

You see, that’s what I mean when I say there were credit default swaps and then there were credit default swaps.

In my Exxon-Mobile example, the credit default swap was insuring against a single corporation defaulting, and in the “CDSs” of our current financial crisis and resulting mortgage meltdown, it was individual homeowners paying mortgages that could cause your bond or CDO (considered to be another derivative) to default. Also, in our Exxon-Mobile example, you owned the bond and in the recent fiasco, you didn’t need to own anything to buy the credit default swap “insurance,” and thereby place a bet against the bond paying off as agreed.

Bond insurance… sort of…

And that’s what a credit default swap is, really… bond insurance. But no one ever wanted to refer to it that way because they were afraid that the State Insurance Commissioners would want to regulate CDSs like they regulate all other forms of insurance, requiring the companies that sold CDSs to hold money in reserve against potential future claims.

Besides, it was argued, CDSs weren’t actually insurance, they just played insurance on T.V.

For example, the buyer of a CDS doesn’t have to own the underlying security that in a sense is being insured against default. In fact, the buyer doesn’t even have to suffer a loss as a result of the defaulting security in order to cash in on the CDS. That’s not very insurance like. And insurance companies manage risk using actuarial data and the law of large numbers to determine appropriate loss reserves, while the sellers of CDSs price them using financial models and attempt to hedge risk using other securities dealers and a variety of transactions in underlying bond markets.

So, since none of the companies that issued credit default swaps ever thought that they’d have to pay a claim related to the insurance they were selling, they didn’t tie up their cash in a reserve account when it could be invested elsewhere, and therefore earning returns. By referring to them as “swaps,” they were completely unregulated, falling under the Commodity Futures Modernization Act (“CFMA”), which was a statute passed in 2000, that removed swaps transactions from any and in fact essentially all substantive federal oversight.

The CFMA legislation was, it’s interesting to note, pretty much rushed through Congress during a lame duck session. It was a rider to an 11,000-page omnibus appropriations bill. So, I think one would have to say, very well done there.

And the end result is that credit default swaps remain entirely unregulated… even after this latest financial disaster, we’ve done nothing to change that, which is sort of like finding out the day after 9-11 happened that we are still allowing passengers to carry box cutters on commercial flights.

What the bankers did…

Okay, so you’re a European bank and you’ve got too many deposits because in your country people still save money, actually.. You’re looking for something to invest in that will help you increase the spread between the interest rates you pay people for their deposits, and the interest rates you’re able to earn by lending.

You need the safest thing you can find, at the highest possible rate of interest… a difficult balancing act for all of us, to be sure.

You could, of course, buy a bunch of triple A rated mortgage-backed securities based on sub-prime loans, but that would increase your reserve requirements, which would reduce the amount of cash you can invest and hence the amount of leverage (read: borrowing) you can employ.

But wait… maybe not. AIG is offering a way for you to have your cake and eat it too. Isn’t financial innovation wonderful?

With the AIG answer, you can forget the Basel II rules by using the unregulated insurance contract called a “credit default swap.” For let’s say 2% of face value, AIG agrees to guarantee the subprime mortgage-backed security you want to buy against default for five years.

As long as it maintained a triple-A credit rating, AIG didn’t have to put up any capital as collateral on its swaps. There was no real capital cost to selling them; there was no limit to the number that could be sold. Of course, as AIG’s credit rating fell, the company was required by its own contracts to post collateral… money… to ensure that it could pay off the claim in the event of a default. And that’s what buried AIG… collateral calls from the likes of Goldman Sachs and many others around the world.

And thanks to “mark-to-market” accounting, as described in FAS 157 and FAS 159, AIG could book the profits from a five-year credit default swap as soon as the contract was sold, based solely on the expected default rate. What the computer said AIG was likely to make on the deal, the accountants would write down as actual profit. The broker who sold the swap would be paid a bonus at the end of the first year – long before the actual profit on the contract was made.

The European bank was now able to assure its regulators that it was holding only triple-A credit securities, and certainly not a bunch of subprime loans given to people without jobs, income or assets. The bank could employ the maximum amount of leverage allowable under Basel II, and AIG could book hundreds of millions in “profit” each year, without having to pony up billions in collateral, or really even invest a dime of its capital.

They even started selling “synthetic CDOs,” which were collateralized debt obligations, but with only credit default swaps inside… no mortgage-backed securities at all… just the credit default swaps that were to pay off in the event of a CDO’s default.

And the bankers who sold these securities and swaps to others around the globe knew they were selling crap in a CDS crapper. They knew the ratings agencies models weren’t tracking the important variables inherent to the loans used in creating the CDOs they were selling. They knew because they were betting against them at the same time they were selling them.

So, what’s not to love?

Well, the fraud part isn’t that attractive, I suppose, but don’t be such a doom and gloomer.

So, our Wall Street bankers sold this scheme all over the planet taking in trillions of dollars and ultimately bankrupting the global financial system and costing hundreds of millions of working class citizens their savings, their livelihoods and their homes. And the profits AIG and the others on Wall Street booked never came true, although the bonuses that got paid out were very real.

On July 10, 2007, Moody’s and S&P downgraded the ratings on 1,032 bond issues, which was less than one percent of the bonds backed by sub-prime mortgages, but the percentage didn’t matter… investors panicked and ran for the exit door. If the ratings on these bonds were wrong, what about the rest… the ALT-A… the Option ARMS… the prime loans… everything was all of a sudden questionable, and within two weeks the credit markets froze solid… banks wouldn’t lend to each other. And the giant write downs began in earnest.

In residential mortgage land, all of a sudden no one could get a mortgage or refinance one. Housing prices, which had already started to cool off as a result of Greenspan having raised interest rates 17 times in a row as of the summer of 2006, now fell off a cliff and kept falling.

Our government just didn’t see what was happening. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, in his recently published book, writing about this moment in history, explains it this way:

“We were just wrong.”

And it may just be that no truer words have ever been spoken, because there’s no question that Mr. Paulson, Mr. Bernanke, Ms. Bair… and all who surrounded them were all monumentally and catastrophically wrong.

The dominoes were falling faster and faster and yet our government did almost nothing to prevent them from falling or even slow them down. As a result, the default rates on mortgage-back securities underwritten in 2005, 2006, and 2007 turned out to be many multiples higher than expected. There are instances in which the securities the bankers claimed to be rated triple A ended worth less than 15¢ on the dollar.

By the end of the calendar year, 2007, AIG reported an $11 billion charge to earnings and managed to raise the capital to cover it. But the writing was all over the walls, the floors, the ceilings, and even the windows. The credit markets were now broken, the days of being able to get a mortgage were over for tens of millions of Americans and as prices fell, defaults increased and the foreclosure crisis would soon be in full swing.

When AIG lost its triple A rating, it had to come up with tens of billions in collateral overnight, in addition to the amounts it owed its trading partners… and there was no way… AIG… the world’s largest insurance company… was bankrupt. Lehman fell the same day… Merrill Lynch was sold in a shotgun wedding to Bank of America. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley were forced to become commercial banks, able to borrow from the Federal Reserve’s discount window, among other things.

The Federal Government stepped in with an $85 billion loan for AIG in exchange for almost all of the equity in the company. AIG’s largest trading partner was Goldman Sachs, and so $20 billion in taxpayer dollars went directly from the people of this country to Goldman’s balance sheet… most of which to be paid out in bonuses over the next year or two. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, who was then heading up the New York Federal Reserve Bank, forced AIG to sign away their right to sue any of the major banks for most of what’s happened.

Because we can keep pointing fingers in all directions if it makes us feel better, but the Wall Street bankers who perpetrated this fraud on our world knew what they were doing as they did it. They did it because they became incredibly wealthy by doing it, simple as that.

The collapse of the market for credit default swaps also meant that the giants of the investment banking world – every last one of them, by the way – with no one to insure their debts, could no longer borrow. Without the CDS market, banks can’t report the real value of the assets (read: CDOs, CDSs, et al). To do so would render them all insolvent and in default with Basel II regulations. Absent AIG’s credit default swaps to provide fraudulent cover, all we can do is play accounting games and pretend that their assets are worth far more than they are actually worth.

The era of the Wall Street investment banker was over. Bankers had leveraged their organizations beyond all reason, meaning that they had borrowed 30:1 or 40:1… or as in the cases of Fannie and Freddie, a mind boggling 110:1 and 174:1, respectively. That means for every dollar the bank carried on it books as an asset, the banks had borrowed thirty or forty dollars. Accounting regulations had to be suspended lest the banks all be seen as insolvent.

Just to fund their operations, our TBTF banks are totally dependent on the Federal Reserve. In fact, things got so bad that the Fed had to change the long-standing rules so that Goldman, Morgan and Merrill could use equities as collateral for trillions in loans.

Additionally, a little known and almost never discussed provision of the TARP bailout bill says that the Fed can pay interest on the collateral it’s holding… a simple, but very effective and yet covert way to pump untold billions in taxpayer dollars directly into the banks without the need for congressional approval.

Without the government having taken these steps, however inadequate and transient, AIG’s failure would have likely led to the failure of every major bank in the world.

But there should be no question… the enabler of the global credit bubble of the last eight years was AIG unregulated selling of credit default swaps without collateralizing the risk. In 1998, there were so few Credit Default Swaps in play that they were hardly worth counting. By late 2009, between newly instituted processes allowing CDSs, which offset each other to be cancelled, combined with the termination of recently paid out contracts, the face value of the CDS market was reduced to an estimated $30 trillion.

And the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill that was signed into law last summer does nothing to address regulation of this volatile and dangerous market.

Seventy percent of the U.S. economy is driven by consumer spending, which has been driven by borrowing over the last ten years. Even if we wanted to do so, we can’t borrow our way back to prosperity this time around, however, because the credit markets are broken for good this time… because they were a fraud in the first place. Our economy has entered a downturn that, before it reverses itself, will force most of us to reduce our standard of living for many if not most of our remaining years. Some believe that foreign spending and spending by the very rich can bring us back, but the numbers just don’t prove out.

Meanwhile, our helpless, hapless, and perhaps hopeless government continues to treat this financial crisis like it’s a liquidity crisis… lowering interest rates and pumping cash into a failed and fraudulent system being run by the same men that brought us here.

Or maybe I’m wrong about all of this… maybe it was all simply the fault of irresponsible sub-prime borrowers who all went out and bought homes they couldn’t afford. Yeah, that must be right. Lower the rates again… extend the tax cuts… print some more dough and pump it into Wall Street’s banks… that’ll probably fix everything.

Mandelman out.

*1 According to the FAA’s Aviation Safety Statistical Fact Book, there are 16 fatalities per one million hours of general aviation, and according to the National Transportation Safety Board, of the airplane accidents that occurred between 1983-2000, 51,207 of the 53,487 of the affected passengers survived. Even if you only consider the 26 most serious airplane accidents during that period, 1,525 of the 2,739 passengers survived… that’s a 56% survival rate. And take out the Lockerbie crash, which wasn’t an accident, but rather a bomb planted by a terrorist, and the survival rate goes up to 61%. So, all told, you being killed in a plane crash is very unlikely.